Jikji is short for Baegun Hwasang Chorok Buljo Jikji Simche Yojeol, meaning Baegun Hwasang’s anthology of great Buddhist priests’ Zen teachings.

Its writer was different from its publisher. Jikji was written by Baegun Hwasang, who was born in 1289 and became a monk at an early age. His Buddhist name was Gyeonghan and Baegun was his pen name. He was a revered monk in Zen Buddhism and died in 1374. After his passing, his pupils Seokchan and Daldam printed their late mentor’s work with movable metal type in 1377. Another Buddhist monk Myodeok supported them with a donation.

Jikji explains the essence of Buddhist teachings. Its main topic is Jikji Simche, excerpted from a famous Buddha quote “Jikji Insim Gyeonseong Seongbul (直指人心 見性成佛),” meaning “See the minds of others through meditation to learn the Buddha’s mind.” In literal translation, Jikji can also be translated as “teaching correctly,” “honest mind,” or “rule rightly.” The pupils printed Jikji in two volumes at the Heungdeoksa Temple in the city of Cheongju in Chungcheongbukdo. Only the second volume has been found and is currently stored at the National Library of France.

Why is Jikji in France?

In the late 1800s, Joseon signed treaties with several western countries, including with France in 1886. In the following year, Victor Collin de Plancy was appointed the first French consul to Korea. He also served in China and Japan. He was a rare book collector. It is unknown when and how Jikji was added to his collection. However, based on its listing on Maurice Courant’s Korean Bibliography in 1901, it is likely to have been collected in the early 1900s.

Jikji was sold to antique collector Henri Véver for 180 francs at an auction at Hotel Drouot in 1911. According to his will, his collections, including Jikji, were donated to the National Library of France around 1950. The French government is not inclined to return Jikji to Korea because it was legitimately purchased, not stolen.

Jikji, buried in unsorted old documents, was discovered by Dr. Park Byeongseon, who worked as a librarian at the National Library of France from 1967 to 1980. Dr. Park didn’t have a background in printing technology at the time. However, after three years of rigorous research, she confirmed that Jikji is the oldest movable metal type print in the world. She submitted Jikji to the library’s book fair in 1972, celebrating UNESCO’s proclamation of International Book Year. That was when Jikji was made public to the world. During the fair, many historians reviewed the book and recognized it as the world’s oldest extant book printed with movable metal type.

Evidence supporting the printing of Jikji with movable metal type

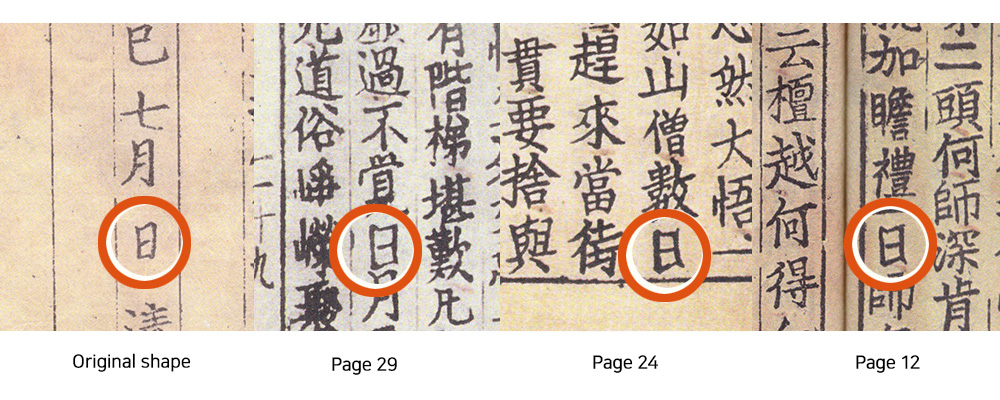

There is ample evidence that supports the printing of Jikji with movable metal type. First, the shape of the letters is slightly different, depending on whether they are printed with woodblocks or metal type. Letters printed with woodblocks are cleaner with some visible knife strokes. On the other hand, letters printed with metal type are less clean with some missing spots in the letters. Letters in Jikji show the pattern of metal type prints, proving that Jikji was printed with movable metal type.

More evidence is found in Jikji itself. On its last page, it specifies who, when, where, and how it was printed. It includes a word “Juja (鑄字),” meaning metal type, indicating that Jikji was printed with metal type. Also, in Jikji, there are letters printed upside down. On page 12, 24, and 29, the upside-down letter il (日) appears in a consistent shape, indicating it was printed by using the same type.